Perhaps the closest analog to a constitution in Saudi Arabia is its Basic Law, a document divided into nine chapters and a total of 83 articles. Interestingly enough, this places Saudi Arabia in very limited company, which includes the United Kingdom and Israel (though the 1948 Israeli Declaration of Independence states that one should be written, one has never been formalized). Though UK membership in the European Union has complicated its own interpretations of law, Parliamentary dictates remain the highest law of the land. Whereas the United States government is required to either adhere to Constitutional law or to make Constitutional amendments in order to make new laws, the United Kingdom’s Parliament is free to pass legislation based on its own estimation of present-day circumstances.

Comparing the 'unwritten' constitutions

On this last note, both the law of the UK and the law of Saudi Arabia have some similarity, in that the current governing body has more say in legal matters than a codified historical document.Another parallel is that both the United Kingdom’s ‘unwritten Constitution’ and the Basic Law of Saudi Arabia establish a constitutional monarchy. The powers vested in the monarch allow them full control over appointing and dismissing those government officials who then interpret and shape the law. In certain other respects, though, the fundamental legal documents of these nations are quite different.

Basic Law and Islamic faith

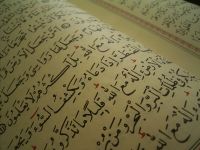

The Basic Law is not, like the U.S. Constitution, a document that is seen as superseding religious principles for moral conduct and effectively denying the legal basis for a theocracy. Whereas the Bill of Rights is seen – in theory, if not always practice – as the starting point for American legal affairs in general and the separation of church and state powers in particular, the Saudi Basic Law is more of a supplement to existing Islamic or Qu’ranic law.

At the outset, it explicitly states that the Qu’ran and the teachings of the prophet Mohammed are the real “constitution”, making one wonder if the purpose of the Basic Law is simply to suggest another source for legal guidance. Indeed, it would be difficult to know what correct conduct is within Saudi Arabia without first having a grounding in Islam: when Article 23 of the law code demands for the state to “[order] people to do right and shun evil”, the precise boundaries of good and evil have to be delineated first. Though there is much about these concepts that is universal, they are “fine-tuned” from one culture and one era to the next, and it is therefore not wise for visitors or foreign workers in Saudi Arabia to assume anything in this regard.

Islamic schools of jurisprudence following shariah law (and its subdivisions of hadith and sunnah) remain far more influential upon legal decisions than the Basic Law’s 83 articles. This is not surprising when considering that the sixth chapter of this guide is devoted to Islam as the basis of governance. This chapter demands that the king (also functioning as prime minister) be the custodian of shariah law, and that all government appointments, from the king’s cabinet on down, follow Islamic precepts in their official conduct and daily lives.

Other provisions of the Basic Law

The fifth chapter of the Basic Law deviates somewhat from religious matters, and establishes Saudi Arabia as a welfare state. It calls specifically upon the state to “[guarantee] the rights of the citizen and his family in cases of emergency, illness and disability” and to “[support] the system of social security and encourages institutions and individuals to contribute in acts of charity”. Subsequent articles call for the state to provide free health care to children. This is notable, since the public image of Saudi Arabia as a monolithically rich country is very much mistaken – some 70% of Saudis are not homeowners, and many do live below the poverty line.

This chapter is also notable for its attempts to quell the fears of critics who believe that a hardline Islamic theocracy is at odds with other forms of progress in knowledge: see Article 29’s insistence that “the state safeguards science, literature and culture; it encourages scientific research”. This chapter also lays the groundwork – if only in a single sentence – for protection of the environment.

Criticisms of the Basic Law

The Basic Law also makes no mention whatsoever of female subjects in the kingdom, whether in relation to human rights or any other issue. Both local critics like the journalist Wajeha Al-Huwaider and international human rights organizations such as Amnesty International (regularly at cross purposes with the Saudi state), have condemned the law over what they see as its enabling ‘non-person’ status for women.

Something to consider, though, when evaluating personal freedom in Saudi Arabia is that its lack of written constitution is not at the heart of these problems. Nations such as North Korea and Syria both have written constitutions, and neither of these nations are exactly known as paradises for civil libertarians. Defenders of ‘unwritten constitutions’ – both those of the U.K. and of Saudi Arabia – will also point to a greater ability for fundamental guidelines to be ‘tweaked’ in accordance with circumstances that could not have been predicted at the time of their original drafts.