In Hong Kong, we recently celebrated the Ching Ming festival, an annual commemoration of ancestors and, consequently, a poignant time of year when family memories are foremost in our thoughts. Thus, delving filially into the past, I often find it tricky to rationalise the circumstances which took hold right from when my parents first arrived in England to my adulthood moves abroad and, thereby, my subsequent typing away here in a small village house located off the old Tai Po Road.

Perhaps I should first explain that my parents migrated to England in the aftermath of WW2, a time of great austerity and unimaginable hardship. Making their way to Nottingham, they secured lowly employment, learned the language and started a family. We were not well off by any means; how could we be? Father was a coal miner; mother was a textile factory machinist. Nevertheless, childhood for me comprised a contented period of working-class warmth. Inevitably, wanting better for their progeny, good schooling and a college education were firmly encouraged.

And so it happened, early days absorbed principally in a rigorous study of engineering, my choice. Family holidays were simple and comprised only a couple of UK breaks and some memorable Sunday outings. In the 70s and within a mining community, more exotic departures would remain alien. Thrill-seeking banners such as Lonely Planet, backpacking, gap year were yet to enter neighbourhood vocabulary. Consequently, we youths possessed scant awareness of long-term travel. Our elders would anyway have thought it decidedly frivolous, with affordability a major concern for all.

For a time, then, far-flung exploits constituted a no-no, and, to be honest, I never felt particularly disadvantaged as a result. I was notably backward in this respect but happy, all the same, with my lot. Unlike today, when some may partake in the wonders of aviation long before the shedding of soggy nappies, my first ever flight occurred at the ripe old age of 26, and that was on my way to begin a new life in Africa. I had never travelled so far before. The change, you’ll agree, was momentous; adventure had finally arrived, but how?

Well, the main catalyst for this unlikely transformation came three years earlier, prompted by a spontaneous rail and camping holiday with a work pal around Western Europe. Such breaks were becoming increasingly popular, and it certainly proved an eye-opener for us both. No coincidence, I sometimes wonder, that he now lives in Sydney and I’m over here. Of course, this was not an instant change, but a gradual evolution in which many factors play out. I had graduated from university, had enjoyed a few good jobs and, you might say, was doing all right. Yet, as time went on, it dawned slowly but surely: this was mediocrity; more was needed.

Changing job, buying a house or getting a decent car had all crossed my mind, but each time I mulled it over, excitement came there none. I was getting nowhere! Still enamoured of that blue-skied, Euro sojourn – maybe a subconscious yearning for distant horizons – ruminations finally turned to a potential spell abroad. But not of a drifting carefree type, hometown sensibilities governed; it would have to be meaningful. There must be a way!

The answer was staring me right in the face: time to exotify that job! Engineers can (and do) work abroad – why shouldn’t I? Events moved swiftly. I’d landed a post in Nigeria, not the most ideal of locations, but, oddly enough, it fitted the bill perfectly. It was a place where nobody ever dreamt of going – it would indeed be a neighbourhood first – and the whole intent undoubtedly reeked of outlandish adventure and a great deal more besides, as I would shortly discover.

As expected, taking all by surprise, colleagues, friends and family were flabbergasted on hearing the news, indeed shocked, and it’s a measure of the change within that a few years previously I would never have imagined leaving Nottingham in such a manner. Now I was, and it couldn’t get any more spectacular. We must remember that in the early-80s minimal travel information existed for this part of the world; perhaps the same could be said today.

I must also clarify that, at this point, apart from being a radical departure and thus nosediving into a rather unconventional lifestyle, I really had no idea how this would progress, let alone end. Furthermore, I needed to remind myself this was not a holiday one could sheepishly bale out of if it didn’t go as planned. It was a serious one-year job with a binding contract; failure to hack it would cost me, payback of incurred company expenses being clearly stipulated.

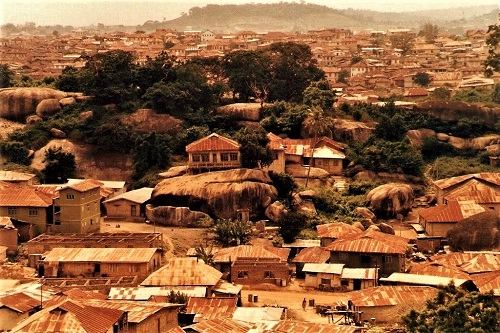

So, off I went, and if anybody should doubt mankind’s ability to travel in time and space, then don’t. I may have unwittingly accomplished this feat on a frosty March morning. You see, I left behind Nottingham, efficient and comfortable transport, the modern world, in fact everything I’d ever known, switching continents and seemingly travelling back in time to emerge within the searing, dry-season dustbowl of Lagos, ugly privations enduring amidst the dilapidated VW Beetles, Peugeot 504s and buses that plied the city’s woeful infrastructure with pitiful groans and grinds. Believe me, a greater contrast would be difficult to imagine; the producers of Dr Who could not have staged it better.

But it’s astonishing how one copes with this, resourcefulness and adaptability to the fore, as life suddenly undergoes a complete recalibration. Consigned to history would be the situation previously known as ‘normal’. Everything would now be different. This was the experience I craved, an induction to the world proper. If I thought life in the UK was getting pedestrian, then indeed travel held the answer; now I was getting somewhere.

I quickly settled into the African flow, but not without a challenge. One could experience horror and enchantment in any given day. Such a posting, it must be said, gifts one the perfect vantage from which to observe third-world problems and, to an extent, first-world versions, too: abject poverty not helped by inadequate housing, sanitation, transport, energy – headaches we engineers were expected to alleviate. We did our best, but sometimes it was difficult to make sense of it all.

At odd junctures, perhaps while driving through the African bush – yes, in a dilapidated VW Beetle – a surreal thought would often take hold that somewhere, seemingly distant in time and space, a parallel universe existed, in which family and friends might be coolly catching a bus, chatting with the greengrocer or sinking a few jars of Shipstone’s ale: same old. A sobering thought, life at home continuing, while I, sweatily navigating a nation’s chronic chaos, gathered tales from a world they couldn’t possibly envisage; who could? The Lagosian hubbub effortlessly enthralled. I felt fulfilled, even though sanity was regularly tested.

To cut a long story short, I enjoyed Nigeria, body and soul reasonably intact, for 30 months, before returning to England. I needed a break and to tackle some professional exams but, needless to say, the travel bug had bitten badly, and it wasn’t too long before the allure of far-off places reared once more. This time it would be eastwards to India, then Japan and Hong Kong. Nigeria was not an easy escapade by any stretch of the imagination, but it was life-changing. My entire outlook had shifted. Whereas Europe was certainly an eye-opener, Nigeria, and subsequent ventures, had allowed me not merely to see but, more critically, to see and perceive, to really understand a place, its people and all its dirty laundry.

African life certainly enhanced my basic survival skills, bolstered by those much-needed attributes of flexibility, patience, tolerance and equanimity. More importantly, there came a decisive ability to embrace further opportunities and leave an old life behind. The significance of this lay in the notion that I could now happily adjust to almost anywhere; I had finally broken out, and there really was a place in the world for me.

Fast-forward 30-odd years then, and here I sit, ensconced in a secluded New Territories village swamped by an array of fabulous flora and fauna, nature breaking in. Nearby, the distinctive shrill of an Asian Koel reinforces how far I’ve come, literally and even figuratively. I’m comfortable with that, though frequently ponder if our identities dilute when moving from place to place, wilfully subsuming those splendidly arresting customs and cultures. It certainly affords the latitude of developing differently without the constraints of one’s homeland environment.

Then again, aside basic know-how and nous gleaned in passing, those dear to me could discern no great personality change, unpleasant or otherwise, behind my new-found worldly phizog. Perhaps travel doesn’t really change us that much after all but simply helps us discover who we really are. It did for me, I think. Or, as my dear parents, having undergone appreciably more demanding travel conditions, may have proffered, ‘It’s all in the genes, lad’.