Expat Focus talks to Stephen Clarke author of his hilarious novel “A Year In The Merde”, and “How the French Won Waterloo – or Think They Did”.

Stephen lives in Paris, where he divides his time between writing and not writing. His first novel, A Year in the Merde, originally became a word-of-mouth hit in 2004, and is now published all over the world. Since then he has published three more bestselling Merde novels, as well as Talk to the Snail, an indispensable guide to understanding the French. Stephen, please tell us about yourself.

I’m very lucky because my main hobby has become my full-time job. After “A Year in the Merde” was a hit, I gave up the dayjob and have been writing full time, a book a year, ever since. Other than that, I play the bass guitar and snorkel, though rarely at the same time.

What prompted your move to Paris?

I was looking for a stress-free job and found it, working on an English-language magazine in Paris. No stress, not much money but 37 days holiday a year. And then they introduced the 35-hour week, and I had even more time to write my novels.

What do you like/dislike about expat life in France?

These days i like that i can stay in touch with my own culture more easily. Before the internet, it was much harder to follow new music, read daily newspapers, watch stand-up comedians (French comics don’t stand up to comparison, no pun intended) (well, yes of course it was intended, as it always is when someone says “no pun intended”). It’s important as an expat to settle in to your new home, but it’s always going to be fun to keep track of the culture you’ve left behind you. I also enjoy that I can buy real French croissants without taking a train or an aeroplane. The thing I don’t like about expat culture is that the beer isn’t that brilliant here, though some small brewers around Paris are now getting their act together.

Your first novel "A Year In The Merde" became a word-of-month hit in 2004, what was the inspiration behind this hilarious book?

Quite simply, everything I went through when I arrived. Plus everything my friends went through. And some things I made up that we could have been through. I didn’t start writing it till I’d been here for ten years, though. I didn’t want to write second-hand clichés, I wanted to write from the point of view of someone who really knows France. And after ten years working for a French company, I hope that came across.

You’ve now published several books which is your favourite and why?

After “A Year”, which I’m especially grateful to because it allowed me to give up the day job, I’m tempted to say “1000 Years of Annoying the French”, because it was a hell of a lot of work, but turned out to be worth it. Only yesterday I met an Englishman who starting raving about how great it was and then almost fainted when I said I wrote it. That is an unbeatable feeling. But one of the books I’m fondest of, in a different way, is “Dirty Bertie”, the story of King Edward VII’s frolicking times in Paris. I went back to original French sources – newspapers of the time, autobiographies of people who knew him, speeches given about him by French politicians, and i really think I’ve contributed something new to the subject. Until now, historians seemed to suggest that he was just wasting his time with actresses and prostitutes in Paris, but in fact he was learning to love France (literally), at a time when Britain was much closer to Germany. And it was his fondness for France that led to the Entente Cordiale in 1904, and meant that Britain and France have been allies ever since. If he’d lived longer, he might even have prevented WW1. Seriously. It’s all in the book. Of course I also concentrate a lot on exactly how much fun he was having, and with whom, which no biographers have done before. Maybe they couldn’t read French as well as I can, but they missed out on some great source material.

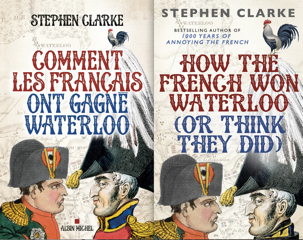

Please tell us more about your latest book" How the French Won Waterloo (Or Think They Did", and if possible include a short excerpt.

There are French historians who love Napoleon so much that they still can’t accept that their hero lost at Waterloo. And their attempts to argue this through are hilarious. They’ve been at it ever since the 19th century, and I’ve tried to analyse all their twisted logic. More than that, though, it’s a book about how Napoleon has actually won the war, if not the battle – he is the most famous historical figure of his time, and France is still a fundamentally Napoleonic country. Lots of French politicians are secretly obsessed by him. And at auction, his hats, his swords, even his socks and hair clippings, fetch absurd prices. France is planning a Napoleon theme park, so soon he’ll be their Mickey Mouse. It’s serious stuff, but hilarious at the same time.

Excerpt included below

What type of audience do you feel your book appeals to?

Anyone who enjoys history, and can read.

As a successful author what tips can you offer aspiring expat writers?

Someone once asked me a flattering question: what’s the difference between a best-selling author and everyone else? I said: nothing at all, except that the best-selling author finished writing his or her book. Take your book idea to its conclusion, make it as good as you possibly can, until you’re really happy with it, until you love it. Then anything can happen.

What are your current projects?

Writing a new “Merde” novel (out next spring, I hope). And repainting my living room wall. The white paint is looking a little grey. Like me. Maybe I’ll paint myself too.

Where can our readers purchase your books and in What formats are they available?

In bookshops, on line, as ebooks, audiobooks, and even printed on sheets of paper and stuck together inside a cover. Can’t remember what you call them.

If you would like to know more about Stephen and the various books he has written please check out his website www.stephenclarkewriter.com or follow him on Twitter @sclarkewriter

Excerpt from "How the French Won Waterloo, Or Think They Did":

Everyone knows who lost the Battle of Waterloo. It was Napoleon Bonaparte, Emperor of France. Even the French have to admit that on the evening of 18 June 1815 it was the Corsican with one hand in his waistcoat who fled the battlefield, his Grande Armée in tatters and his reign effectively at a humiliating end. Napoleon had gambled everything on one great confrontation with his enemies, and he had lost. The word ‘lost’, in this case, having its usual meaning of ‘not won’, ‘been defeated, trounced, hammered’, etc.

No one seriously disputes this historical fact. Well, almost no one . . .

Let’s look at a few quotations.

‘This defeat shines with the aura of victory,’ writes France’s former Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin in a recent book about Napoleon.

‘For the English, Waterloo was a defeat that they won,’ claims French historian Jean-Claude Damamme in his study of the battle, published in 1999.

A nineteenth-century French poet called Edouard d’Escola pre-empted this modern doublethink in a poem about Waterloo when he prefaced it with a quotation to the effect that ‘Defeats are only victories to which fortune has refused to give wings.’

Astonishingly, it is obvious that in some French eyes, where Napoleon is concerned, losing can actually mean winning, or at least not really losing.

This despite the fact that after the Battle of Waterloo, Napoleon was ousted from power, forced to flee his country, and then banished into exile on a wind-blown British island for the rest of his life. The only victory parades in France in the summer of 1815 were those by British, Prussian, Austrian and Russian troops as they marched along the Champs-Elysées, past Napoleon’s half-built, and rather prematurely named, Arc de Triomphe.

And yet today, visitors to Waterloo, just south of Brussels, might be forgiven for thinking that the result of the battle had been overturned after a stewards’ inquiry, and victory handed to the losers (AND SO ON…)