Bookstores, universities, market squares, and cafés are four things that make a city worth spending time in.

Some time ago in Krakow, we happened upon the world’s first bookshop, opened in 1610 and still a bookstore today. Walking around this city, we passed a half-dozen other bookstores, as well, including some specializing in rare and antique volumes.Krakow is also a university town. The 650-year-old Jagiellonian University (Academy of Krakow), founded by Casimir III the Great, is one of the oldest and most important in the world. Its many notable matriculants over the centuries have included Nicolaus Copernicus.

These hallowed halls of education continue to attract the best and brightest from around Poland and beyond. This student population is an important part of the Krakow scene and keeps the centuries-old city lively.

This time of year these uni students are earning tuition money working as tour guides and café wait staff. They speak English and are eager to discuss their studies, their lives in Krakow, the future of Poland, 20th-century history, 21st-century politics…

Krakow’s market square is the biggest in the world. That simple statement doesn’t give you a sense of this plaza. In this space is a town hall tower, several palaces, three churches, and, in the center, the enormous Cloth Hall, originally, in the 13th century, a covered market and today a two-story stone structure that houses dozens of vendor stalls on the ground floor and the Gallery of Polish Art upstairs.

These structures fit within Krakow’s Market Square with football fields of room to spare, creating a bright, wide-open scene that draws you in from every side and every angle.

We drove to Krakow from Prague and arrived after dark, feeling tired, hungry, and impatient. We checked into our hotel and then rallied with the kids to go in search of dinner. When we turned the corner and had our first glimpse of Market Square, our mood changed. Hard to do anything but smile when faced with such a spectacle.

At least 30 restaurants and cafés border Krakow’s central square, all with outdoor tables and all full to overflowing every evening of our peak-season visit.

Throughout the square—roaming from table to table at the outdoor restaurants, positioned at the foot of the bell tower, wandering around the Cloth Hall, and on stage in the central band stand — are musicians… accordion duos, brass trios, and string quartets, some exceptionally talented. Even Lief was persuaded to drop coins in several hats.

At the edges of the square, white horses pull white carriages, clip-clopping, clip-clopping tourists around the many notable sights of this cobblestoned old town. Here and there, craftsmen show off their skills, throwing pots or forging iron.

By the time we got to Krakow, we’d toured many dozens of castles, churches, towers, and museums from Lisbon and Paris to Budapest, Bratislava, Prague, and points between. Krakow’s Market Square offered a welcome reprieve from more touring.

“You all go on and visit that museum without me,” I suggested more than once to my culture-hungry children. “I’ll meet you in the square when you’re finished…”

Then I’d escape for a few minutes alone at a square-side café to sip sparkling water or Prosecco and savor the passing show. While Budapest we found to be a city for partying… and Prague a city with a past that inspires exploration and discovery… Krakow is a city for settling in and soaking up.

Books and ideas… trade and conversation…

These things, then, are Krakow’s historical context, and they are alive and well in its historical center.

However, in Krakow, as elsewhere in the former Eastern Bloc, after the Commies saved the Poles from the Nazis, they moved in to impose their own brand of regulation and restriction. Just beyond the borders of Krakow’s old town is the evidence of how Stalin and company squeezed and strangled the life out of life here.

The contrast between what the communists built in Krakow and the city’s old town is dramatic and, for anyone who appreciates architecture or city planning, demoralizing.

However, the sea of concrete-block high-rises that today surrounds Krakow’s old quarter wasn’t the Soviets’ first idea for how to house their new Polish comrades. The Poles didn’t embrace their new Stalinist leaders at first (or ever), so “Uncle Joe” got the idea to show the people of Poland just how great life under Soviet rule would be.

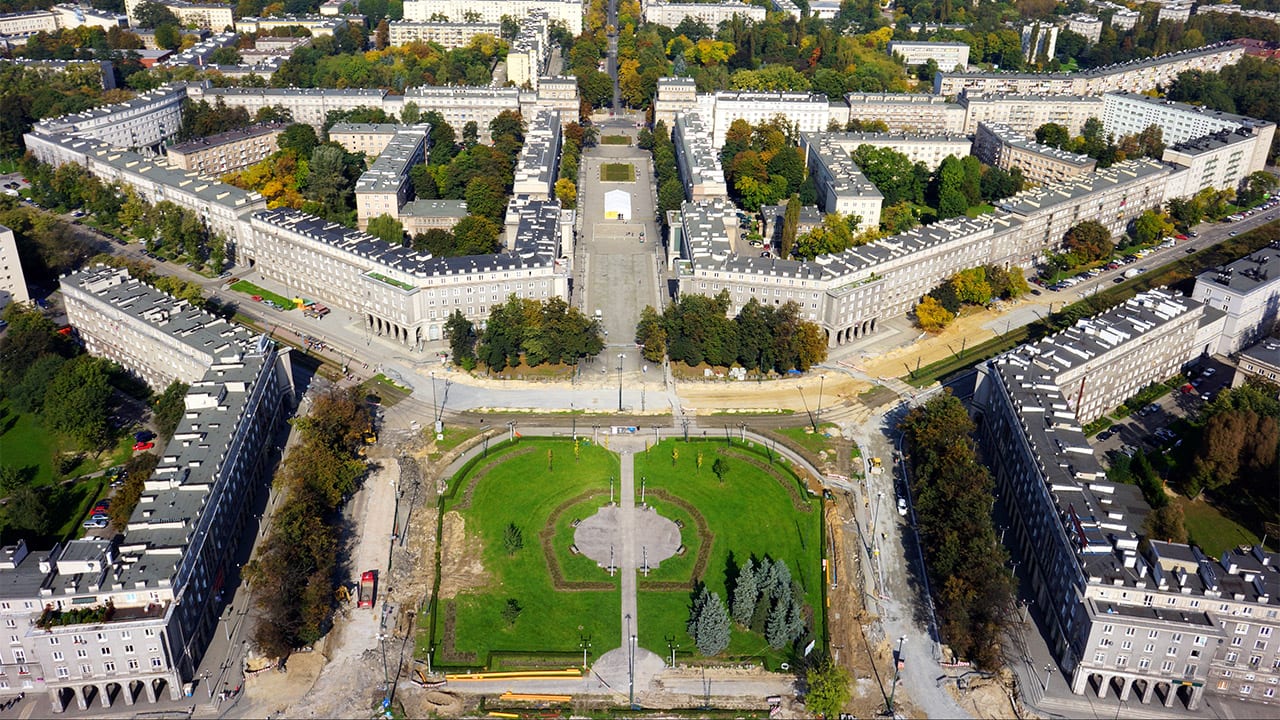

In 1949, Stalin decided to build a model city, a Communist Utopia that he called Nowa Huta (New Steelworks). In this ideal workers’ suburb, located 20 minutes from central Krakow, everyone would be equal.

Stalin and his planners conceived their city as a new Paris. Just like the City of Light, said Stalin, only better. The architecture is reminiscent of central Paris, with white stone facades, tall arcades, ornate moldings, archways, and balconies, and the city is organized around wide boulevards.

“They told everyone the wide streets were so the city would be like Paris,” our guide said. “Really it was so they could roll their tanks through easily, which they did often.”

Every worker relocated to Nowa Huta was given an apartment, and every apartment had high ceilings, parquet floors, and central heating. Remember, everyone was equal.

“Only, as my grandfather used to say,” the young Polish lady who toured us around Nowa Huta explained, “some people were more equal than others. The party leaders living in Nowa Huta got the biggest apartments with the highest ceilings, and the better windows…”

Everyone in Nowa Huta got an apartment courtesy of Uncle Joe and also a job… at the Lenin Steelworks that he located just outside his new city.

“Where did the money come from to build all this?” I asked as we stood in the central square of Nowa Huta looking up and down the main boulevard at row after row of structures.

“Borrowed money… mostly from the Chinese,” our guide explained.

“That was part of the problem. After Stalin died, no one else in the party was willing to continue investing in his Nowa Huta scheme. That’s why this section here,” she said, pointing at the map, “was never built.”

Nowa Huta was left undone, and, post-Stalin, the Communist city planners prized efficiency over everything. Thus the square concrete boxes that blight the landscape as far as you can see in some places.

Today you can tour all this recent history in the company of a Crazy Communist Guide. The guides aren’t communist… only the tours.

You’re driven around in a vintage Trabant. The drive was a highlight of the program. Climbing in and out of these tiny plastic cars requires some gymnastic maneuvering. Some Trabants have heat; some don’t. None have air-conditioning… or ventilation. Even in winter you must drive with the windows down to survive the carbon monoxide gas that flows inside the vehicle.

Our guide for the crazy Trabant tour was one of the many pretty and smart Polish university students we encountered.

“As a kid,” she told us, “I used to tell my parents that I would never live in Poland when I grew up. I imagined anywhere and everywhere must be better than here.

“Then I spent a year in the United States, working as an au pair… and another year in Portugal and elsewhere in Europe… and I realized that these other places aren’t perfect and Krakow is not so bad.

“Right now,” she continued, “we have less than 10 percent unemployment. It’s possible to get a good job and to have a good life here today. I think I’ll stick around after all…”