In last month's column (my first) I mentioned the tendency of expats of all classes and origins to feel an affinity with one another. We share a contempt for the anti-immigrant policies and attitudes of what I call The Immigration Monster – the Civil Service Immigration Department, the Committees and Boards packed with political cronies, the MLAs (elected Members of the Legislative Assembly, our parish parliament) and of course the solid minority bloc of native-Caymanian voters who keep the policies and practices in place.

It was not always thus. Until recent decades, Caymanians welcomed immigrants. The very first settlers probably landed around the time of the English navy’s capture of Jamaica from Spanish soldiers in 1655. There were no indigenous people in Cayman, and it was a natural refuge for escaped African slaves and English indentured servants, and deserters from the English and Spanish armies and navies. (Spanish troops and planters had occupied Jamaica for six or seven generations before the English capture – enslaving and exterminating the local Arawak natives.)In the three Cayman Islands, the refugees were beyond the reach of Jamaican law, at least for a while. Down at the lowest of social levels, there is and was no slavery, and no racial distinction. After a few generations in Cayman, there would not have been many pure-blood Africans or Europeans. (Similar circumstances applied in the slums of London at that time. A surprising number of native Londoners today carry African genes from slaves who had escaped their local English masters either permanently or temporarily.)

In time, the Law arrived. A 1670 Treaty with Spain acknowledged as English any and all islands in the western Caribbean containing a predominance of English settlers. By such a casual reference did the outlaws of Cayman come to be ruled from Jamaica and not Cuba. Official land grants were made by the English Governors of Jamaica (British ones, after the union of the Parliaments of Scotland and England in 1707), to gentry already living in Jamaica. They brought their African slaves over to establish and work plantations of coconuts.

Piracy became a significant cottage-industry, and there are contemporary reports of surprise attacks on passing merchant ships by low-slung local boats hiding in mangrove coastal areas. “Wrecking” – luring passing ships onto local reefs and looting them of their cargoes – was a useful fallback industry. So was turtling – catching wild turtles in the sea and selling them to ships that had escaped the wreckers’ lures.

Four or five generations later, slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire. The white landowners had to free all their slaves, but they kept their land grants. As happened elsewhere, the freed slaves either stayed on their former owners’ land as nominal sharecroppers or settled into new areas as dirt-farmers or fishermen.

On Grand Cayman (the largest island), the Africans and Europeans mixed a great deal more freely than in most places. Immigrants – black and white, mostly by way of Jamaica – brought new blood to a community that never bothered to keep track. There are white Caymanians with some African ancestry and black Caymanians with some European ancestry – white and black being precise colours, in Caymanian usage, not broad ethnic definitions. Most Caymanians are brown-skin, from light brown to dark brown. There is a mild disinclination among the darkest Caymanians to call themselves black, and a refusal by the whitest to identify with white immigrants. There are only “Caymanians”. In very recent years the term “white people” has come to be used to signify middle-class European immigrants, but it is an artificial construct – and a semi-humorous one, actually.

Some home-grown Caymanian boat-builders were commissioned to provide sailing boats for cargo routes along the seaboards of North America. Beginning in the 1930s, Caymanian seamen were recruited by National Bulk Carriers, a large merchant-shipping fleet whose American owner had been raised in one of the several US ports with family connections to the Islands. These seamen’s skills were put to good use by Britain during World War II. I once spent a fascinating few hours listening to a Caymanian veteran of my father’s generation who had served on Arctic convoys to northern Russia.

After the war, men not employed on the cargo ships reverted to subsistence fishing and farming. That phase lasted until the late 1960s when Britain’s Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO) chose Grand Cayman to be the successor to Nassau, Bahamas, as Britain’s tax-haven of choice in the Caribbean.

By the colonial ethics of the time, it probably made sense to import tax-haven professionals from Britain and Canada to service the international clients, and to limit the involvement of the natives to jobs with lower educational requirements. That semi-racist plan soon fell afoul of local aspirations, bringing about a stand-off that led to the forced hiring and promotion of under-qualified native Caymanians with no relevant exposure or experience outside the Islands. That situation still exists today. (The topic has been pretty much beaten to death in my blog postings, beginning with one titled “Cargo Cult” in November 2010; see the archives.)

Application of this rule in all sectors of the economy has resulted in woeful inefficiencies, famously low levels of productivity, and an unnecessarily high cost of living. Also, regrettably, the societal tensions between natives and expats mentioned in my April column for ExpatFocus.

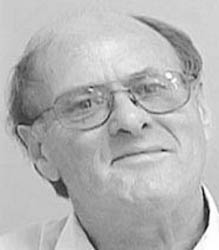

Gordon Barlow has lived in Cayman since 1978. He was the first full-time Manager of the Cayman Islands Chamber of Commerce (1986-1988) – a turbulent period when the Chamber struggled to establish its political independence. He has publicly commented on social and political issues since 1990, and has represented the Chamber at several overseas conferences, and the Cayman Islands Human Rights Committee at an international symposium in Gibraltar in 2004. His blog www.barlowscayman.blogspot.com contains much information on life in Cayman, written from the point of view of a resident and citizen.