Have you ever found yourself in the midst of a teeming conurbation and wondered, somewhat despairingly, where on earth do all these people come from? Well, here in densely populated Hong Kong you can find yourself contemplating that little conundrum on a quite regular basis. And from where indeed is a wonder, for when the British first started sniffing around here, eventually taking up residence in 1842, it was little more than a barren rock as Lord Palmerston famously noted.Of course this was not entirely true as the barren rock back then was home to a few thousand presumably indigenous fisherfolk, farmers and pirates undoubtedly miffed by, though this is not specifically recorded, the foreign big guns and trading houses butting in to change all that forever. Anyway, to cut a long story short, trade and thereby population increased hugely over the decades for Hong Kong to evolve as the significant, commercial powerhouse it is today.

Now, of course, we all appreciate that colonialism is morally reprehensible but after the British nabbed Hong Kong and ruled it as a commercial colony, things happened which perhaps shouldn’t have. For blessed with stable governance, rule of law, education and jobs, the barren rock acted as a magnet for all sorts of folk who consequently arrived in droves. Not only Asia’s oppressed and hard-up fleeing unimaginable poverty and persecution in search of a better life – think countless Chinese from across the border and 320,000 Vietnamese boat people for starters – but also many others including those from the world’s more affluent nations in search of opportunity and adventure abroad. There was simply no stopping them.

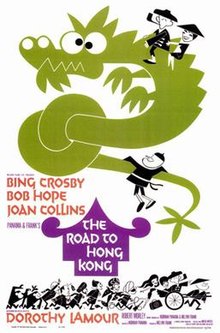

On that theme, I recently watched the 1962 movie The Road to Hong Kong, the final part of the successful, long-running Road to… series, which had me contemplating what an enormous melting pot this city thus became and how everybody’s road of arrival contrasted greatly; perilous for some, a piece of cake for others. With opportunity knocking all sorts of people fetched up here. By plane, ship, road or even swimming, they arrived in their hundreds of thousands; though for a significant swathe it wasn’t quite the non-stop, song, dance and silliness routine created by Bob Hope, Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour (though I should say Joan Collins as the leading female in this movie, poor Dorothy being relegated to a cameo).

And so from those few thousand fisherfolk back in 1842 our population now pushes a staggering seven million; timeline considered, an admirable expansion even those hard-bonking indigenes would have had their work cut out to achieve, and anyway with men out fishing, farming and pillaging all day I doubt if much time remained for that sort of carry on. No, this major population increase occurred mostly in the post-war years and continued right up until the 80s, fuelled by mainland Chinese escaping umpteen political upheavals to attain their Holy Grail: colonial-flavoured safety.

So I’ve often wondered who the true Hong Kong indigenes might really be. Could anybody nowadays trace their lineage back to those hardy villagers of yore, unlike say the UK where the current fad for genealogy might link you back to 1066 and all that. Possibly not, though here most will doubtless have more immediate ancestors – parents, grandparents, great grandparents etc. – to thank for their presence in the territory; they who showed considerable guts and guile in upping sticks and escaping a lunatic communist regime.

I can’t help consider therefore if Hong Kong might be one of the few major world cities where only a small minority of those we dodge on our clamorous, sun-beaten streets possess indigenous ancestry. And what anyway constitutes a Hong Konger? Perhaps we’re all immigrants of sorts – it’s a question of how far back we look. After all, the Hong Kong identity was forged by an east-meets-west quirk of history; indeed it was never quite British nor was it ever quite Chinese. Today that feeling widely persists; in my view it’s what makes the territory such an intriguing place to be and a truly international one at that.

Looking in more detail at the swelling of our ranks, the plight of the Vietnamese boat people in the 70s and 80s received considerable news coverage especially in UK, possibly as much of the rescue and relocation was performed by the Royal Navy, merchant ships and the Hong Kong government. Consequently, several soon to be overcrowded refugee camps were established, camps from which many were allowed to stay in the territory thus becoming valuable members of society, while others were repatriated homeward and some resettled in far-off countries such as the UK. The system wasn’t perfect, it was painfully slow and cumbersome, but it worked eventually. In fact my partner Hilary and her colleagues in the Peterborough social services helped settle in many of those who were subsequently relocated to England.

But, contrastingly, minimal publicity was evident for the mainland Chinese and their stab at freedom, those who against all odds stealthily risked the wrath of army and police border patrols, dogs and barbed wire fences on both sides, or those who thought bugger-this-for-a-game-of-soldiers and, as I mentioned earlier, no joke, defied sharks, cold water, strong currents and marine patrols by swimming to the other side! Some trusted their escape to sampans and rafts, though being easier targets to spot they were thus routinely rounded up by the marine police and taken in.

And so attracted by the bright lights of Hong Kong they tried and tried again, but if on one golden attempt they could somehow reach uncaptured a known relative’s home they would be deemed safe and could apply to stay. I have a good friend here in the village where we live whose father did exactly that – seems many people here have a story to tell, mine is tame in comparison!

The incoming numbers are indeed staggering, according to Gavin Young’s books Slow Boats to China and Slow Boats Home written in the 80s, interviews with the relevant authorities revealed that a quarter of all Hong Kongers in their twenties had, in those few years previously, arrived this way. In numeric terms, roughly 178,000 mainlanders were attempting entry annually of which 110,000 were illegal; of these, 90,000 would be caught, taken to a police station, offered a hot meal and then, after a good rest, returned to the border from where their attempt would undoubtedly be re-thought and re-launched. This was the circular economy, 70s- and 80s-style. For those unfortunates who didn’t make it, their putrefied remains, 450 per year reportedly, were fished out the sea or retrieved off beaches – not a pleasant situation at all.

Although few people in this politically correct world claim to be advocates of colonialism, for balance it might be worth mentioning now that the number of chancers attempting to beat a reverse path out of Hong Kong is, unsurprisingly, not referenced but I think we can assume the list to be rather short. The Hong Kong government meanwhile had, since the post-war years at least, been moving heaven and earth to accommodate the newcomers with one of the most ambitious public housing and welfare programmes seen anywhere. Needless to say, be it boat people or mainland border crossers, interesting parallels might be drawn with the handling of the recent refugee crisis in Europe. Worth remembering is that Europe is a huge landmass, Hong Kong as I always like to compare, is half the size of Nottinghamshire with only half being habitable; the strain on services was immeasurable but the handling admirable.

The mass immigration scenario also proved a fertile hunting ground for the less scrupulous members of society, the people traffickers, those keen to profit from the misery of others. They and countless scammers keen to exploit the desperate and vulnerable necessitated yet further investigative and surveillance operations by the overstretched Hong Kong police and army who generally did a competent, humane job.

That considered, perhaps the storyline of The Road to Hong Kong is not as absurd as it initially appears. In the early scenes Harry Turner (Bing) and Chester Babcock (Bob), a proficient scamming duo, were busy in Calcutta trying to flog a DIY interplanetary flight kit. This amazing piece of kit, demonstrated disastrously by Bob Hope, consisted of a metal helmet with a horizontal propeller atop together with a harness attached to a line and hoist – you can imagine the rest. Anyway, I won’t give the entire plot away in case you’d like to view the movie one day, only to say that Harry and Chester became mixed up with The Third Echelon, a shadowy moneyed organisation, hell-bent on destruction, based on The Peak and, consequently, the pair arrived in Hong Kong in a somewhat unorthodox way (don’t ask!).

I, like many other privileged folk, arrived here by more conventional airplane to take up a pre-arranged job, and a good one too. Unfortunately the start of my Hong Kong life was not entirely auspicious, marred by the airline misplacing my suitcase and leaving me for a couple of days with nothing but the clothes I stood up in. Although this pissed me off greatly at the time, I’ve since learnt, in view of the unfortunate scenarios mentioned herein, that it could have been an awful lot worse – so I won’t bang on about it!

Back in the today’s real world however and Hong Kong’s magnetic charm remains undiminished, still seducing people from across the world; the opportunity’s here all right but will ones fortune be readily forthcoming? Probably in most cases folk won’t do too badly though obviously there’s no guarantee. The notion of not finding out however is still too much to bear for some and they continue to arrive in numbers, all sorts of people, the rich hoping to get richer and the poor in search of an imagined Eldorado – those for whom just being here is seemingly enough.

It’s funny how things change and today, with tables turned, the mainlanders no longer have any need to risk barbed-wire fences or the treacherous swells of the Pearl River estuary. For this is now Chinese Hong Kong and with the illegal Chinese immigrant consigned to history almost anyone can more-or-less enter at will, suitcase full of cash, to buy up as much territorial property as is legal to do – and they do, pricing many a Hong Konger out of their own market!

So there you have it, fancy a life-changing gamble on a spot overseas? You could do a lot worse than choose Hong Kong, and no, you won’t have to encounter The Third Echelon, sidestep ferocious dogs or side-paddle ravenous sharks unless, as one of those faddish extreme travellers, you’re really into that sort of thing! The welcoming of newcomers is a testament to Hong Kong’s generosity of spirit, the modern city now built on an unlikely amalgamation of nationalities. Teamwork you’d call it in today’s business parlance, everybody bringing a quality they can contribute. It’s strange that although I was born in the UK to an immigrant family, I’m now myself an immigrant in Hong Kong; significantly though, and here’s the rub, I feel perfectly at home here, perhaps more so than I ever did in England.

Post Script: Readers will know that in these articles I often like to provide a link back to my birthplace of Nottingham; amazingly, The Road to Hong Kong movie does exactly that though in a daft and quite tenuous way. In one scene the great David Niven appears, his character having retreated to a Tibetan lamasery to learn by heart, with the benefit of a memory enhancing wonder drug, the novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover – written by Nottinghamshire’s very own DH Lawrence of course. Not an easy task and one I’d certainly have trouble keeping up, so to speak. It’s a nice movie touch however, though rest assured I won’t be following suit anytime soon!