As a spotty-faced, teenage oik, I’d no idea engineering would take me halfway round the world. So in marking the 200th anniversary of the Institution of Civil Engineers, commemorations of which will align with the UK government’s Year of Engineering campaign to get youngsters thinking STEM, here’s my bit extolling the virtues of what’s on offer: jobs, locations and project diversity – of which, blowing up where I‘d worked, don’t be jealous now, is indeed a good example. Read on!Today, therefore, I’m wearing a few hats and dealing with career advice, career enhancement and, taking it one step further, stuffing that career of yours into a suitcase and taking it on an extended trip abroad. This article might thus be aimed at children, should they be at a loss as what to do or study when the time comes, parents should they be in a similar quandary, not to mention those committed engineers who might be recently graduated, recently chartered or recently bored.

Of course there are many branches of engineering: electrical, mechanical, aeronautical, marine, environmental, chemical and production to list the more popular and of course civil, where I live. Civil, if you think about it, shapes the very world in which we live even though most people, if asked, haven’t a clue what it’s all about – be honest now, do you? So, not only shall I take a brief stab here at demystification but, mixing in a little spice, explain how it offers not only an engaging career but one that can whisk you effortlessly away to a destination of your choosing. I’ve divided this into a few sections starting with the obvious, just to show how it can all happen.

How did I become an engineer?

In all honesty I don’t remember ever deciding to be an engineer, I sort of drifted into it; but having got there I was very pleased that I did as it certainly led to a life of strange and exciting things. As for any early influence, we grew up in the futuristic Thunderbirds era which often featured scenes of engineering calamity: the Empire State Building collapsing, a runaway monorail heading for impending doom and bridge failures to mention a few. Looking back now I’ve a feeling the late great Gerry Anderson may have had it in for civil engineers.

But never mind, in real life things don’t often happen that way because of civil engineers though such TV programs may have planted a 21st Century subliminal message in my generation. I also remember my parents buying me a Meccano set for Christmas which provided not only hours but years of nuts, washers and pulley wheels turning up in all manner of awkward places; if my parents ever rued the day they bought me this it was stoically never shown.

At school I showed an aptitude for technical drawing and art, though physics and maths were poor and so the draughting option, guided by teacher Mr Aldred, led me to an engineering apprenticeship of the old-fashioned sort. Incidentally, apprenticeships are back in fashion nowadays and can provide an alternative route for youngsters to obtain a degree while simultaneously earning a wage and not having to incur, thereby, considerable student debt.

I was placed under the wing of chief engineer Mr Ron Storer, a sprightly septuagenarian who, for some absurd reason, saw something in me and took me on, training me in all-things engineering with a few life-skills thrown in for good measure. Ron was one of those engineers – a wealth of experience – who knew exactly what needed doing, when to do it, and doing it very well. I couldn’t have asked for a more accomplished or fascinating mentor – I was hooked.

Academically, day-release courses at Nottingham College in building technology followed by a full-time degree in civil and structural engineering at Nottingham Trent University added considerable polish to the product and off I went. This might sound a slightly tortuous route by which to forge a career but nowadays it doesn’t necessarily have to be that way. For most, it will start with a STEM-influenced secondary education, progressing to A-levels and then university – simple!

Why choose engineering?

Although it’s a slightly hackneyed phrase, when civil engineers insist that no two days are ever the same it’s true. They really aren’t and even then the fields in which we work are numerous and distinct: as the Institution of Civil Engineers’ website explains: ‘Civil engineering is everything that’s built around us. It’s about roads and railways, schools, offices, hospitals, water and power supply and much more. The kinds of things we take for granted but would find life very difficult to live without’.

Of course to that list we could add dams, airports, harbours, public health, environmental, heritage sports facilities and particularly IT with the advent of Building Information Modelling; you name it for This is Civil Engineering to quote the Institution’s strapline and you could find yourself working for government, councils, utilities, NGOs, commercial organisations, insurance companies, building contractors or consultants, and that, you have to admit, is quite a decent choice.

In my last job, on secondment at a power station, my remit extended not only to providing new plant and building facilities but also to the refurbishment of existing stock. The mixed workload included geotechnical assessment of rock anchors to the surrounding hill slopes, marine works to the shore, coal jetty and cooling water culverts (often with professional divers), seabed dredging to accommodate Cape-size tankers and, slope-stability of an expansive ash lagoon embankment. More conventional civil works comprised roads and railways to convey heavy machinery. Offbeat tasks required chimney inspections (a good head-for-heights a must!) to assessment of coal stock levels, via a correlation of borehole logs and aerial stereoscopic photos. All in all, an interesting day’s work!

Civil engineering therefore is a profession which provides enormous leeway in creativity and variety; you’ll often be given a blank sheet and it’s down to you and the project team as to how it all proceeds.

Working with a professional set of people can be challenging and yet mentally stimulating and of course, seeing your ideas come to fruition is an extremely satisfying conclusion, even better when it’s something by which society benefits and you can see it clearly every day.

Many of the world’s problems today and in the future will require engineers to play an ever important role; typically, addressing global warming, minimising carbon impact, adapting cities for a rapidly growing population, urban regeneration, mass transit systems, coastal defence, stability and safety of energy, water and food supplies – society’s pressing problems which will need to be tackled swiftly, smartly and sustainably.

Are you up for the challenge? Are you ready to transform lives?

If so, let’s get down to the nitty-gritty and as you’re dying to ask I’ll tell you that an engineer’s remuneration is indeed acceptable, you’ll be well-respected (but more so outside the UK) and, if you’re that way inclined, receive numerous benefits and opportunities to travel the world. Interestingly, a recent Big Bang Fair (the biggest STEM event for young people in UK) reported how some attendees had failed to appreciate the ‘opportunities to travel’ which engineering evidently affords. You readers of course now know better, but do think about it! Are you ready to embrace that all-important life changing opportunity?

But why go overseas?

In a nutshell, because it’s great; great for you that is and great for your career. As current ICE President Robert Mair stated recently, ‘You can get fantastically concentrated experiences if you go overseas’; and indeed it is so. Within days of arriving in my first overseas post (Nigeria) I knew I’d be stretched. Never before had I attended a site meeting with 23 participants comprising nine nationalities or be tasked with the structural design, virtually singlehanded and minus computer, for a 19-storey building necessitating a wind load stability analysis and, architecturally, comprising an unusual floor-type of which design-wise I was somewhat inexperienced; and all this at quite an early age. Needless to say, this was way in advance of anything I’d undergone in UK and it launched me upon a very steep but nonetheless exhilarating learning curve – I think I’m still on it!

It’s true to say then that one certainly attains a higher level of responsibility abroad than might otherwise be expected at home and, being at the sharp end, encounters with management and clients take place at a similarly higher level. Not only do you find yourself to be a more visible representative of the company, doing no harm at all to those career prospects, but also of your country, personal behaviour having a significant bearing on local perception.

It will certainly broaden your mind entering an unknown world as regards not only business etiquette but the social etiquette expected in an entirely different culture. Immersing yourself in the local way of life, maybe learning the language and making friends will certainly add excitement and heighten the charms of wherever you end up; life might be slower, more patience might be needed, things might not always pan out as planed – don’t worry, let it roll. A word of warning though, beware the dreaded culture shock, it does happen but, with a little of what I mentioned just previously, it can easily be tempered.

All in all I feel it’s safe to say you’ll have the time of your life and even if things don’t quite turn out as expected, you’ll have experienced something completely unusual and, of course, go home with enough great memories to bore family and friends to tears for years to come – believe me, there’s a lot of mileage to be had from that!

On the technical side there’ll be much on-the-job learning as you may well end up having to offer advice in areas you might not be totally familiar, external design loadings may differ particularly in areas prone to climatic effects, earthquakes and tsunamis. This, alongside the cultural diversity of living and working abroad where local building regulations and ordinances may be very different to those back home.

And one’s method of working may also require tailoring to local conditions; by example, in some regions a materials shortage might influence the way we design and build. Rather than specify steel member sizes as required by calculation, it might first be necessary to find out what items can be sourced locally and then, working backwards, try to arrange them into a meaningful and economical design. Quality of manufactured goods might also be an issue if working in areas without adequate quality control, consequently their use in load-bearing locations would require serious consideration; you get the idea.

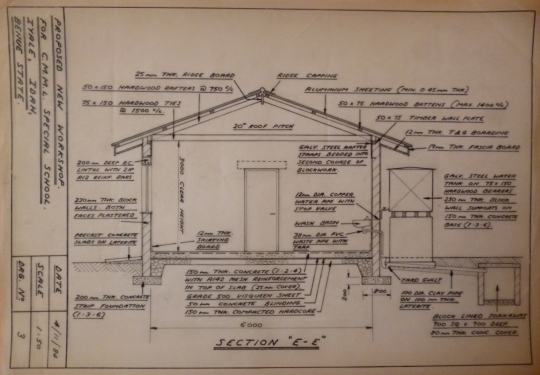

By the way, that early technical drawing skill stood me in very good stead later on in life. When attempting to get stuff built I produced an enormous number of what I refer to as kitchen-table drawings and sketches, A3 or A4 size, very often in the most primitive of conditions and directed at people who might not readily speak my language but would eventually be required to build whatever was shown; this demonstrates that you don’t necessarily need language to read and understand an engineering drawing if clarity and simplicity are key!

So this is a life which certainly suits someone with an adventurous streak, someone with a little ambition who’s prepared to take a risk. Overseas then – convinced? Bags packed? Let’s go!

How to gain work overseas

Not as difficult as you might at first imagine. The obvious way is to check the job ads in the various engineering journals; it won’t be too long before something comes along – it happened twice for me, Nigeria and Japan, six years apart. Failing that, watch out for special open-days held by some of the larger employers or one of the frequent international job fairs which occur up and down the country. Social media and word-of-mouth by the way can also yield positive results. It seems there’s barely a week goes by without an email offering me a temptingly wondrous life in Australia or New Zealand; the shortage of engineers is clearly a global problem.

Alternatively, there are a number of NGOs who partner with local companies worldwide to empower the more impoverished communities, via the skill of engineering, to achieve their basic needs; this could be via the construction of bridges, adequate shelter, simple water supply and treatment etc. Although many such organisations currently operate, here are four examples to be going on with:

• Bridges to Prosperity

• Habitat for Humanity

• Engineers Without Borders

• Engineers Against Poverty

Further thoughts on living overseas

For a little bit more on how I came to work abroad please take a look at The Accidental Expat and An Offer I Couldn't Refuse, two of my previous Expat Focus posts.

In the hope of offering excitement and inspiration to the student, gap-year traveller or young professional, I recounted some of my overseas time in the book Chartered Territory – An Engineer Abroad, a collection of both travel- and career-related anecdotes. Give it a look if you’re not too sure what a life abroad can do for you.

Some home and away favourites

To give you an idea of what your job might entail here’s a few I’ve worked on previously:

Well, as things are built to last, I still take pride in the roof design of the Royal Concert Hall Nottingham (UK), the main structural girders of which required complex welded joint calculations as well some tricky geometrics in positioning the acoustic ceiling panels below. It was all completed in time however for Elton John, little did he know, our eyes cast nervously upwards, to warble merrily away at the opening concert in 1982.

The BBC Droitwich Transmitting Station in Worcestershire (UK) provided experience of another sort. The steel lattice masts, two of them, required maintenance in the form of tensioning numerous guys to the design load followed by a precise theodolite alignment to ensure the mast ended up plumb within the broadcaster’s tight tolerance. After all, wouldn’t want the BBC controller effing and blinding down the blower having just had it in the neck from Angry of Aylesbury who wasn’t receiving Radio 4 as licence dictates. Now that wouldn’t do at all, but thankfully the phones remained silent. The masts incidentally were 213 m (700 ft.) tall and it may well have been here, upon such narrow steel platforms, seemingly closer to heaven, that my head-for-heights was grippingly honed!

A voluntary project I contributed to whilst in Nigeria consisted of a new workshop for a special school in Idah; it made a pleasant change to the larger commercial projects we were working on at the time and, for me, marked a return to more basic building methods. It also presaged the first of many of those kitchen-table drawings I mentioned earlier (see photograph).

And then came the blowing up of where I worked in Hong Kong and I always joke that no matter how urgently many people might crave this scenario, few would ever get the chance to do it – well I did so there! Of course, there was no psychotic or malicious intent on my part and not a white coat to be seen, the whole ‘sane’ activity was supervised by an experienced contractor as part of a controlled explosive demolition.

It was a unique job to be involved in. It comprised the felling of five 150 m tall concrete chimneys – the final concluding demolition of the Tsing Yi Power Station where I first worked after arriving in Hong Kong six years previously. Although preparation works, pre-weakening and planting of explosives, took weeks the demolition was achieved swiftly in only ten seconds flat. Imagine that? It was indeed a spectacular sight to witness all five chimneys falling simultaneously and one of the few jobs I’d worked on which attracted significant media attention. We also achieved the seemingly impossible by getting Hong Kong Air Traffic Control on side and halting arrivals into the super-busy Kai Tak Airport; fear of shockwaves necessitated this precaution as the flight path guided planes directly above the blast zone.

As a further measure of the varied projects in which we engineers seem to get involved there came my way a chicken farm in Nigeria, finalising a Russian/Japanese/USA pre-fab timber hotel design in Seattle (long story), a golf course in Guam and cooling water culvert inspections down in Singapore; interesting jobs, interesting locations – what more can you ask?

Conclusion

So, This is Civil Engineering and what do you think? Hopefully, you now understand a little about what it can offer in terms of career development and opportunities abroad.

I’ve tailored this article to reflect my own career path, if only to show what can be done and that on reflection I’ve generally practised what I preach. You might have realised by now that although I qualified as a civil engineer, structures is the discipline in which I decided to specialise simply because I enjoy it and there’s nothing more to it than that – don’t worry, you’ll find your niche too.

Engineering is certainly a challenging career, I won’t dress it up, it isn’t always easy and you will face struggles. The rewards however are immense and believe me you will be stretched. It certainly stretched me and going overseas stretched me even further, but not to breaking point – I’m here to tell the tale and very much better for it. Did it make me a better engineer? Not sure. I’d like to think so but you decide, or ask my previous bosses, if nothing else I’d like to think it made me a better person and you can’t ask for more than that.

I must also point out that, in terms of our younger readers the content of this article is aimed not only at boys but girls too, so parents in a quandary please take this into account.

This is the end, and in conclusion I’ll simply say that engineering is a great career; not only that but doing it overseas can yield a valuable cultural experience too – I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. How about you? Interested? Time to act!