Okay, maybe not Greek but the subject of Chinese had me spouting similarly when I first landed in Asia many years ago, especially the written form which has remained a source of fascination not to mention great torment ever since. At least the Greek alphabet is vaguely familiar via algebra and physics, so learnable methinks; even reading and writing French at school seemed manageable but as for those unfathomable Chinese characters, well, where the hell do you start?This is a problem of course facing anyone who ventures off to a country where the written form is not reliant on the basic Latin alphabet. Moving to a foreign land and having a stab at the language is indeed an admirable trait, though it soon became clear to me from the off that most Far Eastern written forms would doubtless baffle anyone, even those with the most amazing linguistic acuity. And yet some folk, seemingly few admittedly and particularly those who had studied Asian languages at a university, do manage it, so not an impossible task either. Having said that, outside of the educational institutions there’s precious little opportunity for tuition in the written form apart from self-study books and evening courses aimed more at arty calligraphy rather than the more crucial get-out-there-and-use-it stuff.

Besides visits to the local Chinese restaurant, my first ever being the Kong Nam in Hurts Yard, Nottingham, and usually after pub-close on a Saturday night, my introduction to the wonders and mystique of Chinese characters came in Japan having taken up an engineering job in the 1990s. Must admit though I didn’t learn too many characters in that time and those I did were generally associated with place names and certain foods recognised whilst travelling around: think Hiroshima and sushi. An interesting aspect to the use of Chinese characters in Japanese is that they are usually supplemented by the indigenous syllabic writing systems of hiragana and katakana, both comprising 48 relatively simple and easy to learn squiggles.

You might think that trying to learn a language with three distinct writing systems – oh what fresh hell is this? – would be enough to give all but the most ardent of polyglots a seizure, and in most cases it probably would. Not in Japan though where it works nicely to our advantage; some texts being presented with a mostly hiragana and katakana mix and thus reasonably manageable, enough to get the gist at least – phew! This syllabic method is also a valuable aid to Japanese kids who have yet to learn the principal Chinese characters at school rather than any clueless foreigners tramping about out there; it certainly helped me when venturing off the beaten track!

I didn’t delve any further into written oriental languages until, two years later, when I arrived in Hong Kong for yet another new job which threw up an unlikely Road to Damascus moment. Well, the road didn’t quite lead to Damascus but it did lead to Tsing Yi Power Station in the New Territories. You see, in those days I used to drive an ageing Mazda, possibly dating from biblical times, to work; this journey entailed periods of little movement at an over-trafficked roundabout known as the Kwai Tsing Interchange. In fact I spent a significant portion of my early Hong Kong life gridlocked at this thoroughly miserable destination until years later, dealing nicely with the old, the powers that be took pity and reconfigured it – believe me, those of you who whizz along the top deck nowadays have absolutely no idea! PS. I soon ditched the car and took the bus.

Anyway, to cut a long story short, in between finger-tapping to some none-driving rock track emitting from RTHK’s morning programme, courtesy of DJs Steve James and Harry Wong, I’d have plenty of time to clock what lay around. It was then that I started to pay more attention to the tantalising Chinese characters adorning the backs of trucks and buses in front or beside me, couldn’t really avoid them, and it wasn’t too long before I realised that four characters at the end of most company names were identical. Thus my Road to Tsing Yi moment, my goodness, I had actually learned the characters for Company Limited with very little effort; this had me pondering that I might just have a chance after all!

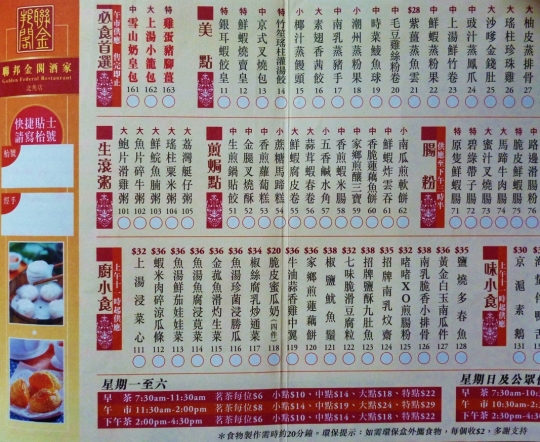

Of course this was in itself a rather limiting discovery and despite feeling very pleased with myself I soon realised that, having subsequently advanced on to Long Vehicle and even Slow Vehicle, it wasn’t going to get me very far in real life – but a crucial start nonetheless. So I decided to apply this new-found deciphering ability to food; now that should be both useful and pleasurable I remember thinking. Conveniently, to suit my purpose, some friends and I had stated to occasionally eat out at a new cha chaan teng (local-style greasy spoon) which had opened near to where we lived. The food was Cantonese/Vietnamese and very tasty, needless to say it soon became a regular haunt.

Whereas in the past I was able to distinguish the various characters for beef, pork, chicken, veg etc. I was never too clear on what the rest of any dish description offered, that is to say how might it be prepared and what will it be served with – so always a bit of a gamble. But lo and behold here lay practical help in the form of a bilingual menu and it wasn’t too long before I’d gotten to grips with both reading and ordering. After all, what better way to learn than with food and beer and lots of it! And I remain ever grateful to the proprietors, Andy and Winnie Chung, for their patient guidance in this matter.

To this satisfactory progress I added the purchase of a Chinese-English dictionary, a very powerful tool indeed and one I’m still using some 25 years later! But first I had to learn how to use it, baffling initially but the listing method is logical once able to determine the component parts of a character; complex at first sight but stare ‘em out for long enough and they soon mystically reveal themselves like those old Magic Eye stereograms. Though having said that, with my inexperience and some frustration, many would not – never mind, I felt practise and perseverance would solve that. And it did! Actually, Hong Kong is an ideal place to learn as in true East-meets-West fashion many things are meticulously presented bilingually, however, stumble across a remote bus stop or a café catering mainly for locals and this mightn’t be the case, so getting to grips with a few basic characters is no bad thing.

I continued this new-found hobby when visiting family in England, only then it was restaurant names which drew my curiosity. Some restaurants, as I’m sure you’re aware, and much to the relief of the postman, Yellow Pages not to mention paying customers, adopt English names generally shadowing their Chinese equivalent – or so I thought! It was only with a little more serious study I realised that in most cases the two had totally different meanings, the Chinese describing some Sino relevance to the restaurant owners while the English often encompassed an exotic vision of what westerner’s might expect, such as Mr Chan’s, The Panda, The Oriental etc.

It was great fun discovering these little linguistic sleights. So going back to the good old Kong Nam restaurant, of which I was recently reminded by a Nottingham Facebook posting, their English name mirrored exactly the Chinese. I didn’t know this back then of course and neither I suppose did anyone else, apart from the Chinese, but the old photo on Facebook proved it. This has taken me over 40 years to work out and you may very well be thinking that it might just have been easier to ask a waiter at the time and you’d be right! And what does it mean? It’s simply a region in China lying south of the Yangtze; Kong meaning big river, in this case the Yangtze, and Nam meaning south. And this nicely demonstrates the power of Chinese characters as without seeing them I may not have made the correct translation even based on the spoken version. The pronunciations I’m now used to would be Gong Naam in Cantonese or Jiang Nam in Mandarin which also highlights the inconsistencies in historically accepted transliterations: think Kowloon to us westerners, but Gau Lung in Cantonese, Jiu Long in Mandarin and you’ll appreciate that things are never quite so clear. The Road to Damascus is indeed fraught with difficulty!

Perhaps now then would be a good time to talk a little about the characters themselves which not only act as a method of communication but are also revered for their artistic calligraphic value. You have to admit there’s something intriguingly beautiful about them and I bet there aren’t too many western households (admit it now!) without some object bearing those darned Chinese characters, if only Made in China! The writing system itself dates back some 3500 years when simple pictographs were used to depict basic meanings. As language developed more complex characters were introduced, often being a combination of the more simple versions.

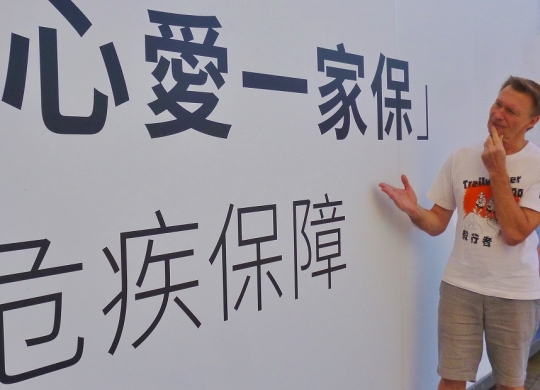

Nowadays there are generally two components to each character, a radical, indicating classification, and a phonetic, indicating pronunciation. Learning to recognise which is which unlocks the mystery and enables the character to be located in a dictionary. For example, the character above my right hand in the photo bears the radical 亻(classification: person) so I thumb to that section in the dictionary where all characters relating to that radical are arranged in numerical order of the remaining pen strokes. Not counting the radical, the number of strokes here therefore is seven and knowing that leads me straight to the character 保, meaning to protect, and yes you’ve guessed it I’m reading an insurance advert. This looking-up process might all sound a bit long-winded to the uninitiated but, as I said, it is logical and with a little practise works a treat.

Anyway, there are 4000 characters in daily use of which knowing some 2000 would be enough to read a newspaper it is said; I still have quite a way to go by the way! Things are complicated a bit by the use of simplified characters in mainland China introduced after the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. The idea being that it would help those with little education to read and write, purists however remain unimpressed as they say it takes away an important part of the language, perhaps it’s similar to not dotting an ‘i’ or crossing a ‘t’ in a Latin-based tongue. What is called pinyin (literally: spell-sound) was also introduced in China in 1958, this is a Latin transliteration of characters and is used on things like street signs, tourist information and transport networks not to mention language text books aimed at foreigners – thankfully therefore it’s possible to study the language and enjoy trips to China without – or before – learning to read it! Interestingly it was Mao Zedong who wished to convert Chinese into a wholly alphabetic system, but it never quite happened and perhaps it’s best that way.

And so my work continues, never a day passes without learning some new character and it still gives me a thrill; though these days I can at least recognise and remember the constituent parts for long enough to reach home and check my faithful, dog-eared dictionary – couldn’t in the past! So, in conclusion I would advise anyone who finds themselves living in a country in which Chinese characters exist to try learning a few; okay, it might (no, will!!) prove a daunting task initially but like everything else there’s a pain barrier to be transcended before attaining the other side, then you’re free to go – as far as you like! Of course, you never know with Mandarin gaining ground in the modern education mainstream you might one day find yourself having to help your children with their calligraphy homework, now wouldn’t that be something!

Indeed, impress family and friends with this new-found skill. And then there’s all that paraphernalia you’ve collected on your Asian travels, imagine being able to decipher them, having that gift. Leaflets, t-shirts, art, porcelain, tattoos, the lot! How satisfying would that be? For me at least I feel that having lived in Asia I should have some idea of what these things are intimating, otherwise I’d feel rather guilty. And now here’s a laugh. To this end, I was flicking through the back pages of a well-known British satirical magazine recently and noticed a small advert for t-shirts produced by a UK company famed more for political and rock band prints. To my surprise they had a new design out bearing a single phrase written in Chinese characters only. What could it mean? Having piqued my curiosity I was intent to know, so I got up close and squintingly scanned the print which was quite small. To my amusement, and ironical amusement at that, it said in a seemingly perfect way: Ignorant westerner who cannot read Chinese. How witty I thought, offensive or self-deprecating? I’ll let you decide! It would certainly give many of my Hong Kong friends a wry chuckle!

Seriously though, do give the study of characters a go, you’ve nothing to lose and it’s sure to open a few doors previously closed to the none reader, otherwise, for evermore, you might find yourself echoing Casca in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, when reporting back to Cassius on his meeting with Cicero: But, for mine own part, it was Greek to me. Don’t let it be.